Its contents are so varied and extensive that this volume should be considered more a library than a book. It comprises 84 different groups of texts, including hundreds of poems, and reflects the intellectual tastes of its medieval patron.

The manuscript’s 1,494 pages includes the Pentateuch (Torah) and Haftarot (readings from the Prophets), Song of Songs and several other biblical texts; the daily, Sabbath and festival prayers, including those for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur; the Passover Haggadah; ![]() Grace after Meals; Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers); assorted legal codes and formulae for agreements concerning marriage, divorce and business partnerships; an arithmetical riddle; laws governing Tefilin and Ritual Slaughter; an abundance of other texts including the Mezuzah; the earliest extant copy of the Hebrew version of the Book of Tobit; a wide range of medieval poetry and the earliest known copy of Isaac de Corbeil’s Sefer Mitsvot Katan, which was composed in 1277.The texts were copied by Benjamin the Scribe who signed his name a number of times, yet left no other information about himself.

Grace after Meals; Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers); assorted legal codes and formulae for agreements concerning marriage, divorce and business partnerships; an arithmetical riddle; laws governing Tefilin and Ritual Slaughter; an abundance of other texts including the Mezuzah; the earliest extant copy of the Hebrew version of the Book of Tobit; a wide range of medieval poetry and the earliest known copy of Isaac de Corbeil’s Sefer Mitsvot Katan, which was composed in 1277.The texts were copied by Benjamin the Scribe who signed his name a number of times, yet left no other information about himself.

A Triumph of Gothic Art

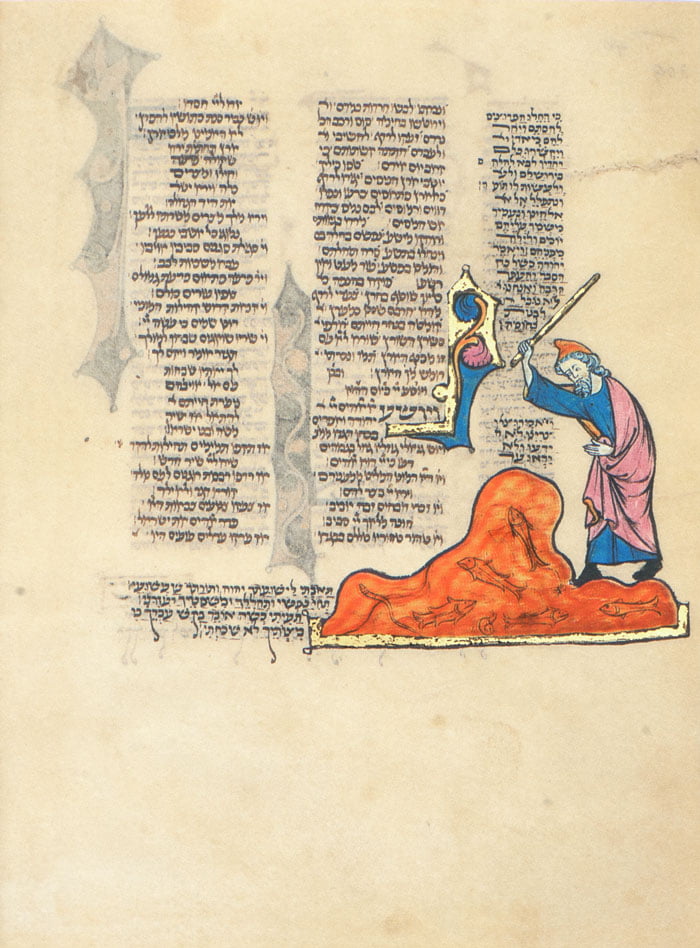

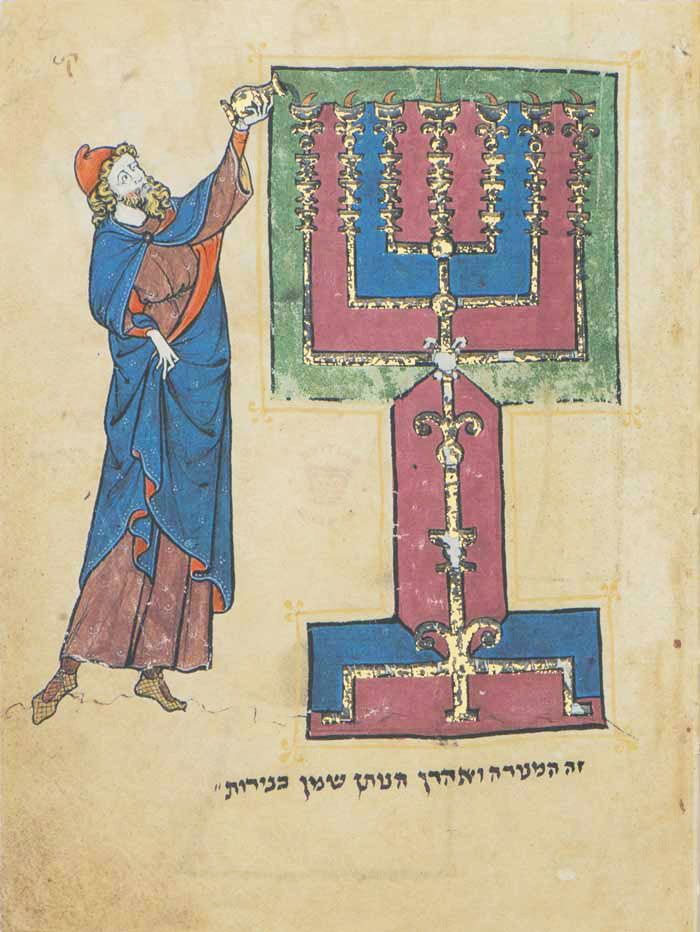

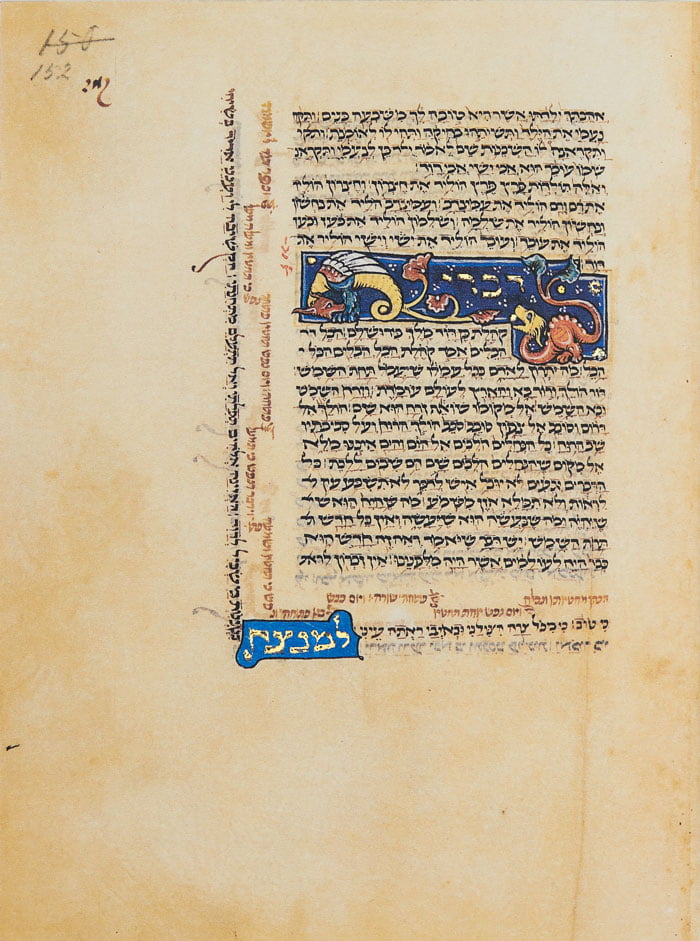

Of no less importance than the texts is the breadth and scope of the elaborate programme of illumination. Most of the 1,494 pages are decorated in the style of the finest artists of the High Gothic period. Ashkenazi Hebrew manuscript illumination reached a peak of excellence during a brief period in northern France, but very few manuscripts from this school have survived.

Add. Ms. 11639 is a masterpiece of its time and place, bearing witness to the artistic quality achieved in northern France. Benjamin the Scribe collaborated with artists whose skill is comparable with that of the makers of the finest contemporary Gothic manuscripts. The numerous full-page miniatures illustrate famous scenes from the Bible, and marginal decorations, their constantly varying arabesques, grotesques, flowers, animals, birds and fishes adorning virtually every folio.

The text points to the manuscript’s origins being somewhere in the region of Alsace. Yael Zirlin, who describes the iconography of the manuscript in the commentary volume, suggests that some may well have been carried out by artists employed by the King in ateliers in Ile-de-la-Cité in Paris. Malachi Beit-Arié’s detailed examination confirms that the initial stages of illumination were carried out by artists in St Omer and subsequent illustrations were carried out by the King’s artists. Most scholars agree that between three and five artists carried out the work.

The myriad decorations adorning the text are a surprise and a visual feast. Many of the full-page miniatures are praised by art historians for their outstanding technique, yet very few scholars have been privileged to hold this treasure.

In a fascinating account, Malachi Beit-Arié writes in the commentary volume that in his view the scribe was the owner of the manuscript.

If that is indeed the case, then he is no other than Binyamin Ha-Sofer (Benjamin the Scribe) mentioned in several colophons in the manuscript. Yael Zirlin, however, presents the view that because seven of the full page illustrations feature Aaron – which is disproportionate to his importance in the scriptures – that the Patron might have been ‘Aaron’.

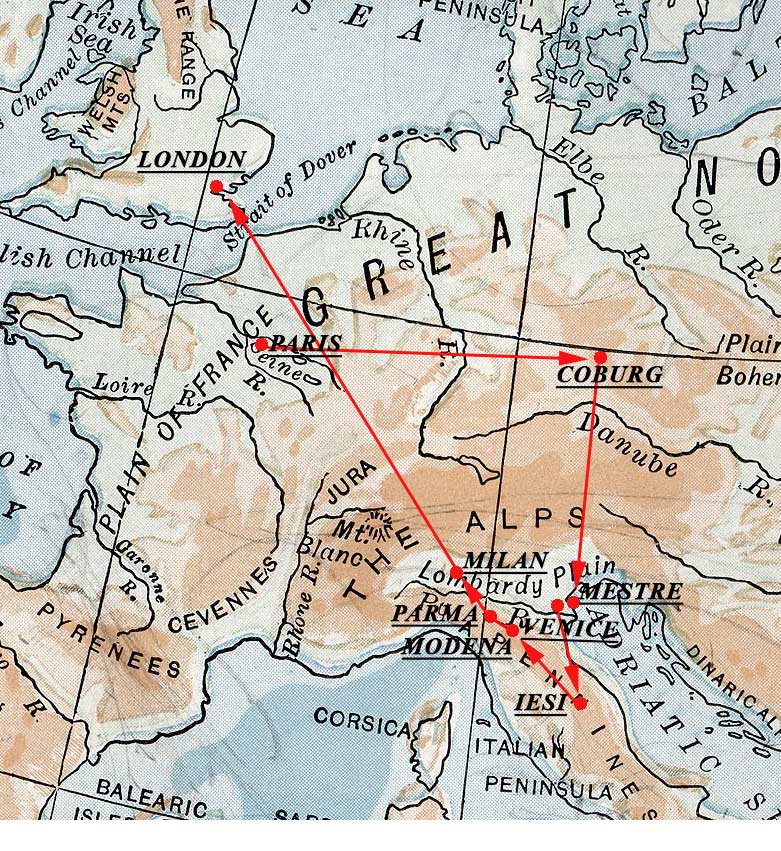

The Fate of the Manuscript – the Miscellany’s 4,000 km journey – 1278-1839

A deed of sale written in a German rabbinic hand shows that the manuscript was sold in 1431 by Samuel b. Hayyim to Abraham b. Moses of Coburg. The manuscript probably left France when its owners were banished during the wave of persecution in 1306. By 1479 it had reached Mestre in Italy and a little later was in Venice. In 1480 it was in Padua and in 1481 in Iesi, near Ancona.

By the end of the fifteenth century it had found its way to north-eastern Italy and was rebound in Modena, near Bologna, in the sixteenth century. The magnificent calf binding that still survives bears the arms of the Rovigo family, one of whose most eminent members, Rabbi Abraham b. Michael, a kabbalist writer, may have owned the manuscript. In the seventeenth century it was examined by a censor and later came into the possession of the Barberini family whose famous golden-bee insignia can still be made out on the binding under a later decorative motif. It is unclear where the manuscript spent the intervening years, although Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIV, Henry IV and Catherine de Medici all collected Hebrew manuscripts. Wherever it was, Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi was able to examine it in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and to include it in his seminal work, Variae lectionis veteris testamenti, in Parma in 1784. The manuscript finally came into the possession of the Reina Library of Milan and remained there until it was sold in 1839 by Maison Silvestre in Paris to Payne & Foss, and then on to the British Museum where it became Add MS 11639, an unparalleled testament to the artistry and culture of thirteenth-century French Jews.

By the end of the fifteenth century it had found its way to north-eastern Italy and was rebound in Modena, near Bologna, in the sixteenth century. The magnificent calf binding that still survives bears the arms of the Rovigo family, one of whose most eminent members, Rabbi Abraham b. Michael, a kabbalist writer, may have owned the manuscript. In the seventeenth century it was examined by a censor and later came into the possession of the Barberini family whose famous golden-bee insignia can still be made out on the binding under a later decorative motif. It is unclear where the manuscript spent the intervening years, although Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIV, Henry IV and Catherine de Medici all collected Hebrew manuscripts. Wherever it was, Giovanni Bernardo de Rossi was able to examine it in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and to include it in his seminal work, Variae lectionis veteris testamenti, in Parma in 1784. The manuscript finally came into the possession of the Reina Library of Milan and remained there until it was sold in 1839 by Maison Silvestre in Paris to Payne & Foss, and then on to the British Museum where it became Add MS 11639, an unparalleled testament to the artistry and culture of thirteenth-century French Jews.

The World of the Manuscript

Northern France, in or near which the manuscript was created, was home in the Middle Ages to a flourishing Jewish community. In 1040, when Rashi was born, Troyes was home to around 1,000 Jews. More about Rashi

Following the Disputation of Paris there were public burnings of cartloads of Jewish books in which the King personally participated. These severely depleted the numbers of Hebrew manuscripts now in existence. In our manuscript, Benjamin the Scribe cites an opinion which he heard personally from Jehiel, who, after the disputation, emigrated to the Holy Land. More about the Disputation

The Facsimile

Introduction

This facsimile affords the reader the rare privilege of personally examining one of the world’s unique manuscript treasures. Slowly turning the pages, one can enjoy the detailed charm of its miniatures, the beauty of its colouring, the texture of its leaves and the unique smell of hand-crafted leather. One is taken on a journey of discovery back to the thirteenth century, for the facsimile brings one almost as close to the original as the patron, scribe and artists were more than 720 years ago.

The stunning clarity of the reproduction of the manuscript is the culmination of the work of Linda and Michael Falter who have established a unique reputation for their ability to replicate exactly the vellum, colours and burnished gold of medieval manuscripts. Each copy is as close to the original as can be achieved. The Falters supervise each element personally in northern Italian ateliers, where their craftsmen work together with them to create some of the finest manuscript reproductions in the world.

“… the ageing effect was probably one of the hardest things to achieve, and you have certainly managed that to perfection”

“The Facsimile is in itself a priceless treasure and I have no doubt whatsoever that its fortunate owners and future library researchers would marvel at its beauty.“

![]() Ilana Tahan M.Phil. OBE

Ilana Tahan M.Phil. OBE

Lead Curator Hebrew and Christian Orient Studies

British Library, London

“… the ageing effect was probably one of the hardest things to achieve, and you have certainly managed that to perfection”

“The Facsimile is in itself a priceless treasure and I have no doubt whatsoever that its fortunate owners and future library researchers would marvel at its beauty.“

![]() Ilana Tahan M.Phil. OBE

Ilana Tahan M.Phil. OBE

Lead Curator Hebrew and Christian Orient Studies

British Library, London

Preparatory Work

Before work could commence, the binding of the manuscript had to be ‘relaxed’ so that the pages could be safely photographed flat without damaging the delicate stitching that holds the leaves together. John Mumford, the British Library’s Senior Conservator, spent days removing the glues applied to the spine when the manuscript was rebound in the sixteenth century in Italy and again in the nineteenth century in the British Museum and carefully preserved the existing sewing undertaken after the manuscript’s renovation by the Rovigo family.

Photography

To ensure minimum stress to the binding, a special cradle was constructed to support the volume during photography. Great care was taken to protect the manuscript’s leaves from changes in temperature or humidity. Large-format transparencies were exposed on a specially-manufactured single batch of Ektachrome film and subsequently processed using the latest quality-control technology.

Colour Separation

Working from the high-quality photographic transparencies, a skilled team in Milan made colour separations by combining sophisticated digital technology with a rare ability to retouch by hand. The Falters then compared proofs, printed on a specially milled paper, with the original manuscript in the British Library in London, and made detailed notes of corrections for each folio. Over several months successive sets of new proofs were made and compared with the manuscript until the closest possible likeness had been achieved.

Paper

Great care has been taken to mill a paper that is as close as possible in appearance, feel and durability to the original skins on which the manuscript was written. To achieve this, the leaves of the original manuscript were carefully measured to determine the opacity, texture and thickness of its vellum. From these measurements a special uncoated, neutral pH vegetable parchment of 125 gsm weight was formulated and milled exclusively for this facsimile edition.

Printing

Michael Falter is his family’s third generation to make a career in printing, and he and his wife Linda closely supervise every stage of production in Milan where they employ the same team of master printers that have worked on each of their facsimiles since 1980. The Falters lived in Milan during the printing process, comparing the final proofs, transparencies and notes with each sheet as it is printed to ensure that the colours of the original are faithfully reflected in the facsimile.

Gilding

The Falters spent years researching and perfecting the special process which enables their craftsmen to apply gold and silver metal leaf to each miniature by hand. Wherever the burnished gold in the original is raised, or where the artists used painted gold, it appears as such in the facsimile.

Binding

The facsimile volume is bound in sumptuous, smooth, dark-brown calf skin which has been gold-tooled to match the original. 23-carat gold has been used for all the tooling, including the central medallion depicting Jacob’s Dream and the distinctive bee escutcheon of the Barberini family to whom the manuscript at one point belonged. The commentary volume is bound in fine white vellum to compliment and contrast with the facsimile. The two volumes are presented in leather-edged beige buckram slip-cases.

Commentary Volume

Vital to this facsimile edition is the substantial commentary volume that contains chapters commissioned from leading experts on every aspect of the manuscript. These include a survey of the historical setting in which the volume was conceived and produced, a thorough examination of the illustrations and illuminations, including their iconography, a detailed description of all 84 groups of texts, a study of its provenance and of the ink, parchment, pigments and binding materials used to create this masterpiece. A full index and glossary completes the commentary volume. Eminent scholars in the field of Hebrew manuscripts and French history have contributed to this, the most comprehensive study of the manuscript ever undertaken. Immense care has been taken over the choice of typeface, paper, illustrations and binding of the commentary. It is printed on 90 gsm Canaletto liscio and bound in fine, natural vellum to complement the facsimile.

Contents of the Commentary Volume

Introduction

Jeremy Schonfield

The Provenance of the Manuscript

Michel Garel describes the political and historical atmosphere in thirteenth-century northern France in which the patron, scribe and artists lived.

The Acquisition of the Miscellany by the British Museum

Diana Rowland-Smith

The Making of the Miscellany

Malachi Beit-Arié explains how the book was constructed and identifies the probable provenance of the scribe and the materials used.

The Decoration of the Miscellany, its Iconography and Style

Yael Zirlin describes the manuscript’s complex iconography and sources

The Binding of the Manuscript

Ilana Tahan

A Piyyut and a French Love-Song

Raphael Loewe

Bibliography

Indices (including Thematic Index to the Texts, Index of Piyyutim, Index of Poets, Index to the Illuminations & Decoration, General Index)

Specification

Codicology

• British Library Add. Ms. 11639

• ISBN 0 948223 219

•Page size 16.5cm x 12.5cm (6.5″ x 5.0″) approximately (sizes vary slightly)

•1,494 pages, folios numbered 0-746

Paper

90 gsm, pH neutral, specially milled vegetable parchment

Printing

Offset lithography in up to ten colours

Gold & Silver

Metal leaf applied in a special hand process to a raised surface on 611 pages where gold and silver appear.

Powdered gold applied elsewhere as it appears in the original.

Cutting & Sewing

Each page has been cut to the exact outline of the original, aged at the edges, then gilded with 23-carat gold and sewn over hand-made head and tail bands prior to binding.

Binding

Smooth, dark-brown calf with 23-carat-gold tooling of the central medallions and edges and blind-tooling on the spine.

Commentary Volume

336 Pages printed on 100 gsm Canaletto Liscio with 23 carat gold fore-edge

Binding in fine white vellum

Gold & Silver

Metal leaf applied in a special hand process to a raised surface on 611 pages where gold and silver appear.

Powdered gold applied elsewhere as it appears in the original.

Cutting & Sewing

Each page has been cut to the exact outline of the original, aged at the edges, then gilded with 23-carat gold and sewn over hand-made head and tail bands prior to binding.

Binding

Smooth, dark-brown calf with 23-carat-gold tooling of the central medallions and edges and blind-tooling on the spine.

Commentary Volume

336 Pages printed on 100 gsm Canaletto Liscio with 23 carat gold fore-edge

Binding in fine white vellum

Presentation

The facsimile and commentary volume are presented in separate elegant, leather-edged slip-cases covered in beige buckram

Dedication Certificate

A specially made certificate can be inscribed by an expert calligrapher, in Latin or Hebrew characters, at no extra cost if requested at the time of ordering.

Edition

This facsimile set is issued in a strictly limited edition of only 330 numbered and 30 Ad Personam copies. Each volume is discreetly numbered by hand inside the leather binding, using minute steel dies, and is accompanied by a numbered certificate carrying the seal of the British Library. The printing plates were destroyed after printing.

The purchase price includes the facsimile, commentary volume, slip-case, shipping container, courier delivery and insurance.

Contents

The North French Miscellany is more a library than a book. The huge range of texts include daily and festival prayers and are mainly of classical and biblical origin but certain items are specific to the time and location of the scribe and artists. Some such texts appear in no other manuscript, making this book the vehicle that ensured their survival.

Main Texts

The Torah (Pentateuch) with illuminated parashah (weekly reading) headings.

The Haftarot (readings from the Prophets) for the festivals and four special Sabbaths prior to Passover – vocalized, cantillated massoretic text with illuminated headings.

The Targum (translation) of the Haftarot for Pesach (Passover) and Shavuot (Pentecost).

Tikun soferim: instructions for Torah scribes, indicating peculiarities of the Massoretic text.

Song of Songs, Ruth and Ecclesiastes; for reading on Pesach, Shavuot and Sukkot (Tabernacles).

Seder hama’arakhah: a weekly cycle of scriptural readings arranged by Elijah ben Menahem ha-Zaken (Le Mans, France, 11th century).

The daily and Sabbath prayers.

Torah readings for new moon, Purim and fast-days.

Pirkei Avot, ‘Ethics of the Fathers’: mishnaic tractate read on Sabbath afternoons during the summer months.

The festival versions of the Amidah prayer.

The Passover Haggadah.

The Targum of the Torah reading for the Seventh Day of Pesach.

The Targum of the Torah reading for Shavuot, including the Ten Commandments and other targumic pieces.

Hosha’anot: a collection of processional hymns for Sukkot (Tabernacles).

Hymns for the festival of Simchat Torah (Rejoicing of the Torah).

A collection of piyyutim (liturgical poems) for the evening services of Pesach, Shavuot, Rosh Hashanah (New Year) and Sukkot.

A list of Torah readings for festivals and fast-days.

Prayers associated with marriage and birth.

Instructions for the Seder (Passover eve) ceremonies.

Blessings over the Lulav on Sukkot, for marriage, and for annulling bad dreams.

Laws of ritual slaughter and meat preparation.

The Funeral Service.

A collection of formulae for legal documents particularly concerning divorce, levirite marriage, loans, partnerships and wills.

Formulae concerning the punishment of informers and traitors.

Decrees of Rabenu Gershom ben Judah (960-1028), the great early Ashkenazi scholar to whom is attributed the ban on multiple wives.

Seder Halitsah: the ceremony for avoiding a levirite marriage.

A collection of piyyutim for the mornings of special Sabbaths, including those of Hanukah, and prior to Purim and Pesach.

Piyyutim for the mornings of Pesach, Shavuot and Sukkot, including for Shabbat Bereshit, on which the reading of Genesis is begun annually.

Thirty-two piyyutim for later in the morning service.

Sixty-six piyyutim for the morning services on Rosh Hashanah.

The services for Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), including 82 piyyutim.

The service for Kol Nidre (Eve of the Day of Atonement), including 32 piyyutim.

Book of Lamentations (recited on the fast of 9 Av).

Book of Esther (recited on Purim).

Calendrical table for 1280-1296, showing when the new moon would appear.

Penitential prayers, including some for Yom Kippur.

Seventy Selichot (penitential prayers).

Sixty-six piyyutim.

Nine Tokhahot (warnings against sin).

Eleven Akedot (prayers on the theme of the Binding of Isaac – Genesis 22).

An index of the texts in nos 37-40 (above).

The text of the Mezuzah (scroll fixed to the door posts), and instructions for preparing Tefilin (phylacteries), based on Maimonides’s code of law.

A cycle of 72 scriptural verses, the prayer for wayfarers, blessings on special occasions, including Grace after Meals and the priestly blessing.

A collection of 9 piyyutim, including table hymns for Sabbath and one composed by the scribe of the manuscript on the martyrdom of Rabbi Shimshon at Metz in 1276.

Calendrical tables and diagrams for the years 1278-1311.

Sefer Mitsvot Katan, by Isaac de Corbeil. This legal code, divided into seven parts for weekly reading, is believed to have been written in around 1277, making this one of the first copies made, to judge by the calendar for 1278 included in the previous text.

A commentary on a poetic code of law by Elijah ben Menahem ha-Zaken.

Commentaries on piyyutim for festivals.

The Appendix to Megilat Ta’anit, an early-rabbinic work on fast-days and the events they commemorate.

Lists of biblical readings, with mnemonic signs.

Sefer Tarshish, a major collection of poems by the Spanish poet and philosopher Moses ibn Ezra (c.1055 – after 1135).

A commentary on the poems for Rosh Hashanah.

A commentary on the poems for Yom Kippur.

Gematria (numerological correspondences) for kabbalistic meditation.

Laws of conduct on festivals and fast-days.

Marginal Texts

Hallel: Psalms 113-118, recited on new moon and festivals.

Book of Psalms.

The Sabbath table hymn, Barukh el elyon, by Barukh ben Samuel.

The Sabbath table hymn, Yatsa devar hamalkah.

Book of Proverbs.

A prayer of praise and of petition for protection.

Book of Daniel.

Books of Ezra and Nehemiah.

A commentary on some of the piyyutim appearing on the same pages as 27 above.

A commentary on some of the piyyutim for Pesach appearing on the same pages as 28 above.

The weekly Haftarot and the preceding and concluding blessings, complimenting those in 2 above.

Book of Job.

An introductory piyyut for Grace after Meals.

A commentary on items appearing in the main panel of the same pages in 36-38 above.

A piyyut including the acrostic ‘Solomon’.

A treatise on the vocalization of the Hebrew Bible.

A treatise on cantillation marks in the Hebrew Bible.

A treatise on the pronunciation of Hebrew.

A poem on cantillation, by a northern-French scholar.

A listing of the large letters included in manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible.

Examples of biblical Gematria.

An arithmetical riddle.

A short text on a messianic theme.

A short text on a talmudic theme.

A short listing of the rabbinic succession from Moses to the editors of the Talmud.

An alphabetical index of rabbis mentioned in the Talmud.

A listing of mishnaic and talmudic rabbis.

A description of those disqualified from acting as legal witnesses.

Book of Tobit. (An extremely rare text in medieval manuscripts.)

The textual evidence for a place of origin around Metz is not supported by the artistic decoration, however. Twentieth-century scholars reached various conclusions regarding the identity and locations of the artists who decorated the manuscript. Some believed the artists to be Jews and others Christian, some saw the paintings as the work of a number of artists and others of a single hand. The precise location and date of each stage of the work, in addition, seemed equally uncertain. However, in the facsimile’s commentary volume, a new certainty emerges: Malachi Beit-Arié’s detailed examination of how its pages were prepared and assembled confirms the conclusions offered by Yael Zirlin, that the initial stages of illumination were carried out by artists in St Omer and subsequent illustrations were carried out by the King’s own artists in ateliers in Paris. Most scholars agree that between three and five artists carried out the work.

More about Rashi As a young man he was able to learn about activities as varied as agriculture, engraving, soldering, weaving and embroidering silk with gold. Rashi later left Troyes to study in Mainz and Worms and when he returned in 1070 founded an academy which soon rivalled and finally supplanted those of the Rhenish provinces.

In 1095-6 Crusaders murdered several of Rashi’s friends and relatives in the course of massacres alluded to in his writings. His three daughters all married prominent scholars and in turn had sons famous for their learning. Rashi is best remembered for his commentaries that have influenced even Christian biblical interpretation. That on the Bible was the first book to be printed in Hebrew, and since he frequently translated unusual Hebrew terms into Old French, his writings are an important source for scholars of French. His descendants and students – who formed the core of a group of talmudic commentators known as the Tosafists – lived in the region for several generations, making it an important centre of Jewish scholarship. In 1240, some time before our manuscript was conceived, Jehiel of Paris, a major scholar from northern France, was the head of the academy in Paris and the main defender of Judaism in the Disputation of Paris held at the court of Louis IX.

In 1288 the Jewish community of Troyes was victim of a blood libel following the discovery on Good Friday, during Passover, of the body of a Christian that had been surreptitiously placed in the house of one of the Jewish notables, Isaac Châtelain.

Following an inquiry carried out by Franciscans and Dominicans, thirteen Jews gave themselves up in order to save the rest of the community and were burned at the stake. A few years later, the Jews of France were banished. By 1308 there was not a single Jew living in the Département of Aube. In 1966, the Rashi Community Centre was built in Troyes, and was designed to serve its small community of some 400 Jews.

The facsimile’s number is blind-stamped into the binding