International Press Reviews

Click images for original articles, country flags for text versions

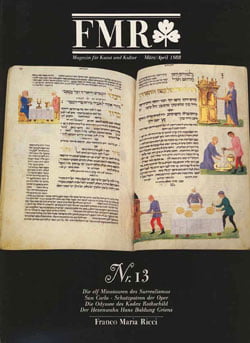

Renaissance of a Hebraica masterpiece

Jewish Chronicle – March 24 1989

Edited by Meir Persoff

NEXT MONTH sees the publication of the Rothschild Miscellany facsimile, one of the highlights of last week’s Jerusalem Book Fair.

The Rothschild Miscellany was commissioned by Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen, probably around 1470, at the height of the Renaissance in Italy. It was a time when artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo executed their greatest achievements.

It was also a time when the Jews in Italy came into contact with all sectors of society and adopted the way of life of the gentile aristocracy. They enjoyed the favourable attitude of some of the great Italian princes, such as the Medici of Florence and the Este of Ferrara.

The prohibition by the Church for Christians to lend money for interest was highly beneficial to the Jewish community, many of whom prospered. The wealthy Jew became a man of the Renaissance, with a taste for letters and art, and a delight in affluent living.

Nonetheless, the Jews never became estranged from their intellectual and religious heritage. This was a period of unprecedented cultural activity among Italian Jewry, producing scholars, artists, poets and physicians.

The Rothschild Miscellany, as it is now known, is the most elegantly and lavishly executed Hebrew manuscript of that era. From its inception, it was planned as a sumptuous work to encompass, in minute detail, almost every custom of religious and secular Jewish life.

The figure drawings and border decorations of the miniatures mirror the rich Italian Renaissance influence and were probably made in a workshop in northern Italy.

Fanciful landscapes, spatial perspective settings and the precision of human and animal representations echo the style of the best artists who worked for the court of the Este in the third quarter of the fifteenth century.

The history of the Miscellany is something of a mystery. From 1832 to 1855, the manuscript was in the Solomon de Parente collectionin Trieste; it was later sold to the Rothschild family in Paris and remained there until it was stolen during the Nazi occupation and reappeared, after the war, in New York.

Someone tried to sell it to Alexander Marx, librarian at the Jewish Theological Seminary, who realised that it had been stolen from the Rothschilds and returned it to them in London.

James de Rothschild was persuaded by Mordechai Narkiss, director of the Bezalel Museum in Israel, that a manuscript of such importance was a national treasure and therefore belonged in Israel. In 1957, de Rothschild sent it as a gift to the Bezalel (now part of the Israel Museum).

The Rothschild Miscellany consists of more than 70 religious and secular works. All have textual illustrations for each festival, and prayers for special occasions.

The secular books include philosophical, moralistic and scientific treatises. The text throughout is accompanied by marginal notes and rabbinical commentaries.

This large collection of miscellaneous yet connected texts became the framework for an unprecedented programme of illumination. It contains a wealth of material illustrating almost every custom of daily life in a Jewish Renaissance household. Of 948 pages, 816 are decorated in minute detail in vibrant colours, gold and silver.

In 1980, when we embarked on the Kennicott Bible facsimile, few believed that the colossal project could ever come to fruition. Five years later the Bodleian Library was moved to write that it was “perhaps the most faithful and exact copy ever to be produced.”

The Rothschild Miscellany proved to be an even greater challenge, for the publisher’s philosophy dictates that a facsimile must be as close to the original as humanly possible. Tremendous efforts were made to acquire the finest materials and craftsmen to impart to each volume not only the presence, but also the feel, of an original manuscript.

We moved to Italy to supervise every stage of the facsimile’s production and, by combining craftsmanship and dogged determination with modern technology, remarkable results have been achieved.

The Rothschild Miscellany was hand-copied and illuminated on foetal vellum, which is soft and translucent. The folios were studied for their thickness, weight and opacity and a new type of “paper,” virtually indistinguishable from the manuscript’s vellum, was specially milled in Italy.

The result is a fine vegetable parchment, with the same natural characteristics of skin, that makes printing on it very difficult.

The printing of the minutely-detailed illuminations, in up to 12 colours, demanded considerable skill and perseverance of the Italian master-printer. Colour separations were made for each of the 948 pages; every one was individually checked against the manuscript in Jerusalem and then re-proofed in Italy (up to four times for each page) until the colour was exactly right.

However, no printing process can adequately simulate the gold leaf in the manuscript and it was decided that the only way to reproduce raised burnished gold was to lay the leaf by hand, thereby achieving the richness and “feel” of the original gold. Thus, on 812 pages, gold was “built up” so as faithfully to reproduce burnished gold.

In addition, the manuscript contains thousands of illustrations with powdered gold and flat gold leaf and this, too, has been applied by hand in the facsimile.

The pages of the manuscript contain the minute pricking holes made by the scribe between which he ruled parallel lines to guide him in the writing of the text. Even these pinsize holes have been reproduced.

The edges of the pages of the Miscellany are brown with age and irregular. In the facsimile, each one has been laboriously cut to exactly the same size and shape as the original, then “aged” and finally gilt with 23-carat gold leaf at the very edges.

As the original binding of the manuscript no longer exists, Dr Mirjam Foot, binding specialist at the British Library, suggested an exquisite Italian binding of the period, worthy of the manuscript, which our craftsmen have copied in minute detail.

The facsimile is bound in fine-grain, morocco goatskin, blind-tooled with bevelled edges, hand-sewn head and tail bands and silver clasps on leather thongs. The Israel Museum plans to rebind the manuscript in the same binding as the facsimile.

The companion volume, edited by the Israel Museum, was written by five eminent scholars, who have discussed the art, iconography, palaeography, liturgy and history of the manuscript in great detail. This volume is in itself the most comprehensive work ever written about the Rothschild Miscellany and is bound to the same exacting standards as the facsimile.

MICHAEL FALTER

The North French Miscellany

Letter from the British Library – 5th March 2004

Dear Linda and Michael,

Last Monday David Way and I opened the box containing the facsimile of the North French Miscellany. Unwrapping the beautiful blue packaging was done with the greatest anticipation and excitement. We were immediately struck by the quality and standard of your work and most impressed at seeing how faithfully and beautifully everything has been replicated.

The palette of colours, the choice of paper that emulates the colour and texture of vellum, the stain marks and fingerprints left in the book, the ink and pigment smudges, the marbled paper on the boards, the gold applied so carefully to the miniatures, are just some of the many delightful features that strike one with every turn of the page.

I also very much admired the ageing effect on the matt leather covers, particularly along the spine, and the delicate erosion of the gold motifs on the boards. David Way said that the ageing effect was probably one of the hardest things to achieve and you have certainly managed that to perfection.

The beautifully crafted and attractively bound accompanying volume is a very important addition. I truly liked the pale creamy colour of the leather binding. An elegant choice indeed! Placing black and white illustrations as dividers between the various research papers has created a very aesthetic effect.

The slip cases too should not go unmentioned for they are attractive, solid and well designed. I particularly liked the brown leather trimmings and the rounded inside block matching the contours of the main volume.

The facsimile is in itself a priceless treasure and I have no doubt whatsoever that its fortunate owners and future library researchers would marvel at its beauty.

Please accept my warmest congratulations on the successful completion of a gigantic and challenging project!!!

We look forward to receiving the remaining two copies to add to the library’s collection.

With very best wishes

Ilana Tahan

Hebraica Curator

Jewish Art – The art of bookmaking

The International Jerusalem Post – June 27, 2003

BY LEORA EREN FRUCHT

Modern technology has made it possible to own an exact copy of a medieval Hebrew masterpiece by a mysterious scribe

Picture King David in a crimson robe, seated on his throne, playing the lyre. Visualize Aharon pouring oil into the menora. These famous scenes from the Bible are among dozens of richly colored, gold-embossed illustrations completed under the guidance of a scribe named Benjamin, who worked near Troyes – the French town where Rashi taught – in the Middle Ages.

The scribe, about whom little is known, collaborated with local artists to illustrate – and possibly commission – what is considered one of the most exquisite and comprehensive Hebrew manuscripts of Medieval Europe, known as the North French Hebrew Miscellany. More a library than a single document, the 1,494-page manuscript was composed around the year 1280 and includes the Pentateuch and Haftarot (passages from the Prophets), Song of Songs, and several other biblical texts; the daily, Sabbath and festival prayers; Pirkei Avot(Ethics of the Fathers); the Passover Haggada; prayers associated with marriage and birth; assorted legal codes for agreements concerning marriage, divorce, and business partnerships; a mathematical riddle; laws governing ritual slaughter; and a wide range of medieval poetry – in all, 84 subjects. To date, the treasure has been kept in the British Library, where only a handful of scholars have been granted permission to examine it because of its fragility.

This month, the public will get a peek at the trove, when the first copy of the manuscript, produced by Facsimile Editions of London, is displayed at the Jerusalem Book Fair, June 23-27.

This is one of the finest, most beautiful Hebrew manuscripts I have ever seen,” says Prof. Malachi Beit-Arié, one of the few scholars to have viewed the original at the British Museum.

Beit-Arié, a former director of the National Library in Jerusalem, has studied some 5,000 Hebrew manuscripts written between 900 and 1540 CE. He also wrote part of the commentary accompanying the soon-to-be published facsimile edition of the North French Hebrew Miscellany which, like the original, contains full-page gold embossed illustrations of famous biblical scenes, as well as marginal decorations of arabesques, flowers, animals, and birds adorning every folio.

“In terms of design, production and complexity, this one is a real beauty,” says the professor of Codicology and Palaeography at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

It is also a rare document. Most Hebrew manuscripts from this period have perished – in part because of the public burnings of Jewish books in which France’s King Louis IX personally participated. There is another less dramatic explanation for the dearth of Hebrew manuscripts.

“While most Latin manuscripts of that time were produced to be kept in royal collections or cathedrals, the Hebrew manuscripts of the Middle Ages were produced for consumption,” notes Beit-Arié. “These books perished over time out of sheer wear and tear.” The North French Hebrew Miscellany is a remnant of that period – one which is surrounded by mystery.

“This work is one of the most impressive achievements of any Jewish scribe of the Middle Ages,” says Beit-Arié, “and yet we don’t know who he was or who his patron was.” “Benjamin the Scribe” has signed his name in several places, but Beit-Arié notes that this name does not appear in any other Hebrew manuscript – and he has studied thousands of them. There is also no mention of a patron.

“This,” he says, “is a great paradox. It is inconceivable that such a luxurious manuscript would be signed by a scribe without mentioning the patron, who must have been more than well off – unless Benjamin produced it for himself.”

Beit-Arié notes that Benjamin must have been an extraordinary man.

“We know he was a scholar. He would have had to have been a learned man in order to compile this unique combination of texts.”

He probably employed top artisans, many of them Christians, to execute the work, particularly the gold illuminations.

The enigmatic Benjamin also composed a poem about a Jewish French martyr, Samson, who was murdered in 1275. That poem is one of many in the manuscript, notes Beit-Arié.

“So he was a scribe, a scholar, a poet, and possibly a wealthy man. Yet he remains an obscure figure in Jewish history.”

While little is known about the master behind the manuscript, much more is known about the fate of the document. The original manuscript found its way into the British Library after a circuitous route. According to the publishers: “A deed of sale written in a German rabbinic hand shows that it was sold in 1431 by Samuel b. Hayyim to Abraham b. Moses of Coburg. The manuscript probably left France when its owners were banished during the wave of persecution in 1306. By 1479 it had reached Mestre in Italy, and a little later it was in Venice…

“By the end of the fifteenth century it had made its way to north-eastern Italy and was re-bound in Modena, near Bologna, in the sixteenth century. The magnificent calf binding that still survives bears the arms of the Rovigo family, one of whose most eminent members, Rabbi Abraham b. Michael, a kabbalist writer, may have owned the manuscript. In the seventeenth century it was examined by a censor and later came into the possession of the Barberini family, whose famous golden-bee insignia can still be made out on the binding under a later decorative motif.

“It is unclear where the manuscript spent the intervening years, although Cardinal Richelieu, Louis XIV, Henry IV and Catherine de Medici all collected Hebrew manuscripts… The manuscript finally came into the possession of the Reina Library of Milan, and remained there until it was sold in 1839 by Maison Silvestre in Paris to Payne & Foss, and then on to the British Museum, where it became Additional Manuscript 11639.”

The reproduction of the manuscript is the result of years of work by the London-based husband-and-wife team, Michael and Linda Falter, who started and run Facsimile Editions Ltd. The company has produced precise copies – in limited editions – of 10 outstanding Hebrew manuscripts, among them: the Alba Bible, a 1430 translation of the Hebrew Bible into Castilian; the Kennicott Bible, a 1476 edition from northwestern Spain, considered the treasure of the Bodleian Library; the Rothschild Miscellany, a 948-page body of religious and secular works commissioned at the height of the Renaissance in Italy; Me’ah Berachot (One Hundred Blessings), a miniature prayer book handwritten and illuminated in Central Europe during the eighteenth century; and the Parma Psalter, a profusely illuminated book of Psalms written and decorated around 1280 in Northern Italy.

“This team is unquestionably the best in the world when it comes to producing facsimiles of Hebrew manuscripts,” says Dr. Binyamin Elizur of the Hebrew Language Academy. Elizur recounts that a senior researcher at the National Library, upon seeing the Rothschild Miscellany on a desk in the library, asked his supervisor how he could obtain the original.

“He couldn’t tell it was a copy. Anyone who has a copy of a manuscript produced by this firm has no need to see the original; they are virtually indistinguishable,” notes Elizur, who dated the Rothschild manuscript.

Producing such high-quality reproductions of ancient texts is a tedious ordeal. Before work could commence on the North French manuscript, the binding had to be “relaxed” so that the pages could be safely photographed flat without damaging the delicate stitching that holds the leaves together. The British Library’s senior conservator spent days removing the glues applied to the spine when the manuscript had been bound centuries ago. To ensure minirnum stress to the binding, a special cradle was constructed to support the volume during photography. All this was done under a controlled temperature and humidity setting to protect the manuscript’s leaves.

A special paper was milled to emulate as closely as possible the opacity, texture, and thickness of the original vellum. Natural wormholes, stains, and pricking in the original skin are faithfully reproduced in the facsimile, and pages were aged where necessary.

A special process was developed to enable craftsmen in srnall workshops to apply gold and silver leaf to each page by hand so as to simulate the metallic leaf found in the original.

The long production process – and limited edition of each volume – is reflected in the cost: Each of the 550 copies of the North French Hebrew Miscellany will sell for almost $9,000. Previous reproductions have ranged from $650 for the Rothschild Haggada to $26,000 for the Alba Bible. Who spends that kind of money on a copy of an old Hebrew book?

Libraries, of course. The facsimile editions are found in dozens of institutions, from Sydney to Santiago, Scotland to South Africa, where they can be studied by scholars. Oxford’s Bodleian, the British Library, Israel’s National Library, and the Israel Museum are regular clientele. The facsimile editions have also becorne a popular gift among statesmen. An Israeli minister gave US president Bill Clinton a Parma Psalter inscribed with a dedication from Psalms “How pleasant it is for brothers to dwell in unity.” Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was presented with a Kennicott Bible, as was former crown prince Hassan of Jordan.

King Juan Carlos I and Queen Sophia of Spain received a copy of the Alba Bible in 1992 to mark the king’s formal retraction of the order expelling the Jews from Spain 500 years earlier. Not all recipients are rich or famous.

Falter says the publications have become popular family gifts. One person wrote in his dedication: “A Gift from beyond the Grave,” and left it to his son in his will. Other ordinary people buy them to commemorate special events, or for donation to their synagogue. Most of the clientele are in the US, Israel, and the UK. Says Falter: “People often buy them to keep within the family.”

Making it real

Michael and Linda Falter, a Jewish couple from London, are the force behind Facsimile Editions Ltd.

Michael Falter is the third generation of a family which has worked in the printing industry since the late 1800s. During a stroll through the British Museum in the late Seventies, Falter saw two pages of a manuscript on display behind glass, and thought what a pity he couldn’t view the whole work. He wondered whether he might be able to use the antique presses given to him by his father to reproduce a Hebrew manuscript. He called a friend, Prof. David Patterson, director of the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies, who told him about the Kennicott Bible, and though it was a restricted manuscript, arranged for Michael to see it.

He and Linda Falter launched their partnership – in life and work – during a visit to Oxford’s Bodleian Library a few days later.

“On our first date he said to me: ‘I’m going to the Bodleian on Thursday. Would you like to come with me?'” recalls Linda.

“I said: ‘I’m sorry, I don’t drink’ – thinking he had said Bodley Inn!”

The two went to the library, fell in love with the Kennicott Bible and “before we knew it, we were on a path of no return,” continues Linda. ‘We soon set across Europe looking for printers, binders, and various experts who would be able to carry out such a complex book. It took us two years to convince the Bodleian that we could complete such a huge undertaking.

“Apparently, Oxford University Press had looked at the project and decided it was too complex.”

It took them more than five years to pro: duce their first facsimile, the Kennicott Bible. But upon completion of the work, the Bodleian Library – and other prestigious libraries – lauded their effort.

The couple, who are both Jewish, read Hebrew only haltingly.

“We may do a summer ulpan so that we are more fluent by the next Book Fair,” notes Linda.

North French Hebrew Miscellany

Medieval History Magazine – July 2004

This little treasure, only 161/2 x 121/2 cm (61/2″ x 51/2″) is a magnificent medieval volume, the most important Hebrew manuscript exhibited by the British Library. A facsimile edition has been produced to the highest possible standards by world leaders in this field Facsimile Editions, London.

The Background to The North French Miscellany

The Miscellany contains all that is important to a Jew, the Pentateuch and Haftarot (readings from the Prophets), the Song of Songs, together with biblical texts and prayers such as those for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

It also provides guidance on rituals regarding Tefillin, (phylacteries – consists of two leather boxes, containing four passages of the Torah, used by Jewish men at prayer) ritual slaughter, the Mezuzah, (parchment with two passages from Deuteronomy written on it, fixed to doorpost of a Jewish house)

Jewish law concerning marriage, divorce and even business partnerships! The volume also contains the Hebrew version of the Book of Tobit, an extremely rare text in medieval manuscripts.

The manuscript originated in northeast France, in the region of Picardy-Artois between 1278 and 1280. Philip III was king of France, having succeeded his father, Louis IX (Saint Louis), in 1270. Louis IX had imposed severe restrictions on Jews in 1219 forcing them to wear the Jewish badge, the rouelle. Philip imposed additional restrictions in 1277 forcing Jews to wear the horned, or `Jew’s’ Hat, in addition to the rouelle. This pictorial evidence dates the manuscript between 1278 and 1280. This date is further confirmed by the inclusion of the earliest known copy of Isaac de Corbeil’s Sefer Mitsvot Katan, a legal code composed in or around 1277.

The manuscript probably left France during a period of increasing Jewish persecution in 1306 reaching Mestre in Italy by 1479 and eventually arriving in Venice. No one knows exactly what happened to the manuscript after that. Catherine de Medici, Louis XIV, Cardinal Richelieu and Henry IV were all enthusiastic collectors of Hebrew manuscripts and perhaps the manuscript was owned by one of these.

The Scribe and the Artwork

Some researchers believe that Benjamin the Scribe, see Folio 306 verso was the sole copyist creating the manuscript for his own use. If this is correct then Benjamin must have been extremely wealthy, since the finest artists were employed and no expense spared. It seems inconceivable that a single scribe could afford to create something so luxurious. Many Jews of the time manufactured silk, sold cloth or manufactured wine from their own vineyards so perhaps Benjamin was a wealthy merchant. It is interesting that Benjamin, having indicated in his colophon that he was the sole scribe, gives no insight as to whom the patron, if there was one, could have been.

The volume contains 49 full page miniatures depicting biblical scenes. It provides pictorial evidence of social conditions and is ultimately a very fine piece of artwork. Almost all of its 1,494 folios are illustrated with grotesques, flowers, arabesques, animals, fishes and birds in the High Gothic style. The Miscellany bears witness to the extremely high standards achieved by the creators of Ashkenazi Hebrew manuscripts at this time.

Folio 354v demonstrates the unity between the written word and magnificent artwork. The page is divided into three columns. One column is enclosed in a lavishly decorated box surrounded by angels, winged animals and grotesques. Within the boxed column the important words are enlarged to double line height and heavily underlined with gilded embossments. In the third column the gilded heading emerges from the mouth of a fictitious animal.

Folio 522r, the Tabernacle Implements, is presented within a gold medallion. The Ark of the Covenant is flanked by two cherubim. At the bottom of the illustration is the Table of Shewbread. To the right is the jar of manna. This is a very rare depiction of the Tabernacle implements and so far as is known does not appear anywhere else in Ashkenazi manuscripts. It comes from the tradition of Spanish bibles.

A sense of humour is visible throughout the manuscript. On Folio 355r marginal decorations serve not only to emphasise the important words, but also to display the artist’s mischievous sense of fun. In the top right-hand corner there is a strange creature with a human face wearing a pointed hat, a reference to the restrictions on Jews at that time.

The Production of the Facsimile

The extraordinary frailty of the original made its reproduction a very delicate operation. Using extreme caution the manuscript was prepared by experts at the British Library. Every page was photographed and great care taken to ensure exact colour matching between the original and the facsimile.

The facsimile is printed on uncoated, neutral pH vegetable parchment, specially manufactured to be as close as possible in weight and thickness to the original skins.

The raised burnished gold leaf of the original has been faithfully reproduced. Gold and silver metal leaf was applied layer by layer and then each folio was cut to match the original and aged where necessary. Where Benjamin’s prickings have survived these have been reproduced together with natural holes present in the skins on their original purchase.

The facsimile is accompanied by a companion volume containing articles commissioned from the world’s leading experts. These provide in-depth explanations of all 84 groups of texts plus facts relating to the manuscript’s original creation. This is the most thorough study of the Miscellany undertaken to date.

Only 360 copies of the facsimile and its companion have been produced and the photographic plates have now been destroyed to guarantee the fidelity of the facsimile.

Frances Spiegel B.A. (Hons.) Dip. Eur. Hum

Adding new gold to the Rothschild Miscellany

Philadelphia Jewish Exponent – January 15 1988

By HELEN DAVIS

JERUSALEM — Five hundred years ago, at the height of the Renaissance, a wealthy Italian Jew, Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen, gathered around him some of Italy’s finest scribes, artists and craftsmen.

His intention was to create the most elegant, lavishly illustrated Hebrew manuscript of the era —a work to rival the sumptuous manuscripts being commissioned by the Roman Catholic aristocracy of Italy.

The result was a masterpiece, an exquisite miscellany of Jewish religious and secular life. The book includes the daily and festival prayers, the books of Psalms, Job and Proverbs, the Passover Haggadah, Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), fables, moralistic stories and treatises.

No one knows what became of Moses Hacohen, but his magnificent miscellany, which was probably written around 1470, survived him.

From 1832 to 1855, the manuscript was in the Soloman de Parente collection in Trieste, Italy. Later, it was sold to the Rothschild family in Paris, where it remained until it was looted during the Nazi occupation.

The manuscript — now known as the Rothschild Miscellany — reappeared in New York after the war when an attempt was made to sell it to Alexander Marx, librarian of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Marx instantly recognized the manuscript as one of the treasures of the Rothschild collection and had it restored to the family in London.

In 1957, James de Rothschild sent the miscellany to Israel, as a gift to Jerusalem, and the original is now in the Israel Museum.

Enter — half a millennium after Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen — Michael and Linda Falter, a young Jewish couple from London with a passion for ancient, illuminated manuscripts.

The Falters had fallen in love with the Rothschild Miscellany and they determined to produce a facsimile edition that would be as faithful to the priceless original as possible, using the finest human skills and the most advanced technology available.

Moreover, the Israel Museum was delighted to cooperate for the enthusiastic Falters had already won themselves a remarkable reputation within the rarified world of collectors, scholars and custodians of ancient, illuminated manuscripts.

In June 1985, after five years of painstaking research, they had produced a magnificent facsimile edition of the famous Kennicott Hebrew Bible, which was written and illustrated in La Coruna, Spain, in 1476, shortly before the Inquisition and expulsion of Spanish Jewry.

The Kennicott Bible — so named after Benjamin Kennicott, an English Christian Hebraist — is one of the jewels of the famous Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

The 500-year-old original manuscript is so frail, and of such immense value, that only 20 art historians and scholars over the past 200 years have been allowed to even study it.

Michael and Linda Falter saw the Kennicott Bible just once, by special arrangement, and immediately decided to create a facsimile edition.

“We didn’t actually decide to create a facsimile,” said Linda Falter. “The Bible decided for us. It was something beautiful that took you away from the nastiness of every day; a lovely thing to be involved in.

“But the challenge of reproducing it without the skills that were available to the creators of the original was formidable.”

Equally formidable was the task of convincing the Bodleian Library and the Board of Oxford University to give the untried Falters a contract to produce the facsimile — and permission to photograph the bible’s 922 pages through optical white glass that was manufactured specially for the project.

Through sheer perseverance and abundant energy, the couple succeeded. It took them a year to find an Italian paper manufacturer who; after much trial, error and expensive research, could mill for them a special paper with a thickness, translucence and “feel” almost identical to the original calfskin vellum.

Then came the search for a printer capable of handling the extraordinarily difficult task of reproducing precisely the Hebrew text and the 11-color illustrations.

Michael Falter, 39, is himself a third-generation printer. He knew the difficulties involved and he scoured Europe for months until he finally found a craftsman in Milan whose work “was astounding.”

But even the gifted Italian craftsman could not find a short cut to applying gold leaf to 12,090 pages of manuscript.

“We finally came to the conclusion,” says Michael Falter, “that the only way to apply gold so that it would feel like the original was the way it was applied to the original —by hand. And that’s just what we did.”

The final problem to overcome was to reproduce the opulent, six-sided, box-binding that had sustained the original Kennicott Bible, keeping it virtually airtight for 500 years.

Britain’s top binderies tried, and failed, to reproduce the original to the Falter’s exacting standards: “We got to the point,” says Linda Falter, “where we nearly gave up.”

They were financing all the trials and research themselves, costs were exorbitant, and the results disappointing.

Once again, it was an Italian who came to the rescue. He produced, just from a photograph, a binding of Moroccan goatskin stretched over wooden boards, embossed with handcut brass dies and faithful to the original in every detail.

When the Kennicott facsimile was finally produced, the limited edition of 550 copies became an instant collectors’ item. The price of the work reflected the superb craftsmanship and beauty of the product.

Before it was actually published, collectors could order the facsimile for a price of $2,900. By the time of publication, it had risen to $3,900, and today, with but a few remaining on the market, economic forces have pushed up the price to around $5,500.

The Kennicott Bibles have become prized additions to private collections throughout the world — the Japanese Royal Family bought 10 —and have been purchased by major universities in Britain, Europe, the United States and Australia.

According to Dr. Martin Brett, a medieval historian at Cambridge University, the superbly produced facsimiles give scholars and the general public access to ancient, priceless works, allowing them to “adore without destroying.”

“Some of these priceless works simply fall apart in your hands,” he says. “You feel their bindings crack — it’s a very uneasy feeling.

“Expertly produced facsimiles solve that problem. Scholars won’t have to keep referring to the original.”

Having proved their ability to faithfully reproduce exquisite manuscripts, the Falters are now faced with an embarrassment of riches. Museums and libraries all over the world are offering their most precious manuscripts for facsimile.

The Rothschild Miscellany, however, was a natural choice for their next venture. An astounding 816 of its 948 pages are richly illuminated and decorated with burnished, flat and powdered gold and silver.

While the Falters and their Italian craftsmen have mastered the basic techniques of facsimile production, the Rothschild Miscellany, which will be published in June, has demanded a great deal of additional research and technical development.

The Falters moved to Milan with their two infant sons to supervise every stage of production, which includes the meticulous checking of each page against the original manuscript in Jerusalem.

They are confident that the finished product — with a pre-publication price of $4,900, rising to some $6,300 after publication — reflect the same devotion to perfection that was poured into its creation 500 years ago.

Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen would surely have approved.

Adding new gold to the Rothschild Miscellany

Philadelphia Jewish Exponent – January 15 1988

By HELEN DAVIS

JERUSALEM — Five hundred years ago, at the height of the Renaissance, a wealthy Italian Jew, Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen, gathered around him some of Italy’s finest scribes, artists and craftsmen.

His intention was to create the most elegant, lavishly illustrated Hebrew manuscript of the era —a work to rival the sumptuous manuscripts being commissioned by the Roman Catholic aristocracy of Italy.

The result was a masterpiece, an exquisite miscellany of Jewish religious and secular life. The book includes the daily and festival prayers, the books of Psalms, Job and Proverbs, the Passover Haggadah, Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers), fables, moralistic stories and treatises.

No one knows what became of Moses Hacohen, but his magnificent miscellany, which was probably written around 1470, survived him.

From 1832 to 1855, the manuscript was in the Soloman de Parente collection in Trieste, Italy. Later, it was sold to the Rothschild family in Paris, where it remained until it was looted during the Nazi occupation.

The manuscript — now known as the Rothschild Miscellany — reappeared in New York after the war when an attempt was made to sell it to Alexander Marx, librarian of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

Marx instantly recognized the manuscript as one of the treasures of the Rothschild collection and had it restored to the family in London.

In 1957, James de Rothschild sent the miscellany to Israel, as a gift to Jerusalem, and the original is now in the Israel Museum.

Enter — half a millennium after Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen — Michael and Linda Falter, a young Jewish couple from London with a passion for ancient, illuminated manuscripts.

The Falters had fallen in love with the Rothschild Miscellany and they determined to produce a facsimile edition that would be as faithful to the priceless original as possible, using the finest human skills and the most advanced technology available.

Moreover, the Israel Museum was delighted to cooperate for the enthusiastic Falters had already won themselves a remarkable reputation within the rarified world of collectors, scholars and custodians of ancient, illuminated manuscripts.

In June 1985, after five years of painstaking research, they had produced a magnificent facsimile edition of the famous Kennicott Hebrew Bible, which was written and illustrated in La Coruna, Spain, in 1476, shortly before the Inquisition and expulsion of Spanish Jewry.

The Kennicott Bible — so named after Benjamin Kennicott, an English Christian Hebraist — is one of the jewels of the famous Bodleian Library in Oxford, England.

The 500-year-old original manuscript is so frail, and of such immense value, that only 20 art historians and scholars over the past 200 years have been allowed to even study it.

Michael and Linda Falter saw the Kennicott Bible just once, by special arrangement, and immediately decided to create a facsimile edition.

“We didn’t actually decide to create a facsimile,” said Linda Falter. “The Bible decided for us. It was something beautiful that took you away from the nastiness of every day; a lovely thing to be involved in.

“But the challenge of reproducing it without the skills that were available to the creators of the original was formidable.”

Equally formidable was the task of convincing the Bodleian Library and the Board of Oxford University to give the untried Falters a contract to produce the facsimile — and permission to photograph the bible’s 922 pages through optical white glass that was manufactured specially for the project.

Through sheer perseverance and abundant energy, the couple succeeded. It took them a year to find an Italian paper manufacturer who; after much trial, error and expensive research, could mill for them a special paper with a thickness, translucence and “feel” almost identical to the original calfskin vellum.

Then came the search for a printer capable of handling the extraordinarily difficult task of reproducing precisely the Hebrew text and the 11-color illustrations.

Michael Falter, 39, is himself a third-generation printer. He knew the difficulties involved and he scoured Europe for months until he finally found a craftsman in Milan whose work “was astounding.”

But even the gifted Italian craftsman could not find a short cut to applying gold leaf to 12,090 pages of manuscript.

“We finally came to the conclusion,” says Michael Falter, “that the only way to apply gold so that it would feel like the original was the way it was applied to the original —by hand. And that’s just what we did.”

The final problem to overcome was to reproduce the opulent, six-sided, box-binding that had sustained the original Kennicott Bible, keeping it virtually airtight for 500 years.

Britain’s top binderies tried, and failed, to reproduce the original to the Falter’s exacting standards: “We got to the point,” says Linda Falter, “where we nearly gave up.”

They were financing all the trials and research themselves, costs were exorbitant, and the results disappointing.

Once again, it was an Italian who came to the rescue. He produced, just from a photograph, a binding of Moroccan goatskin stretched over wooden boards, embossed with handcut brass dies and faithful to the original in every detail.

When the Kennicott facsimile was finally produced, the limited edition of 550 copies became an instant collectors’ item. The price of the work reflected the superb craftsmanship and beauty of the product.

Before it was actually published, collectors could order the facsimile for a price of $2,900. By the time of publication, it had risen to $3,900, and today, with but a few remaining on the market, economic forces have pushed up the price to around $5,500.

The Kennicott Bibles have become prized additions to private collections throughout the world — the Japanese Royal Family bought 10 —and have been purchased by major universities in Britain, Europe, the United States and Australia.

According to Dr. Martin Brett, a medieval historian at Cambridge University, the superbly produced facsimiles give scholars and the general public access to ancient, priceless works, allowing them to “adore without destroying.”

“Some of these priceless works simply fall apart in your hands,” he says. “You feel their bindings crack — it’s a very uneasy feeling.

“Expertly produced facsimiles solve that problem. Scholars won’t have to keep referring to the original.”

Having proved their ability to faithfully reproduce exquisite manuscripts, the Falters are now faced with an embarrassment of riches. Museums and libraries all over the world are offering their most precious manuscripts for facsimile.

The Rothschild Miscellany, however, was a natural choice for their next venture. An astounding 816 of its 948 pages are richly illuminated and decorated with burnished, flat and powdered gold and silver.

While the Falters and their Italian craftsmen have mastered the basic techniques of facsimile production, the Rothschild Miscellany, which will be published in June, has demanded a great deal of additional research and technical development.

The Falters moved to Milan with their two infant sons to supervise every stage of production, which includes the meticulous checking of each page against the original manuscript in Jerusalem.

They are confident that the finished product — with a pre-publication price of $4,900, rising to some $6,300 after publication — reflect the same devotion to perfection that was poured into its creation 500 years ago.

Moses ben Yekutiel Hacohen would surely have approved.

The Rothschilds Reunited

Women’s League Outlook – Fall 1989

Dr. Lynne Heller

In the spring of 1950, Dr. Alexander Marx, Librarian of the Jewish Theological Seminary, received an intriguing letter from a Berlin book dealer who was offering for sale to the Library an Italian 15th century, illuminated Hebrew manuscript of extraordinary quality. Enclosed were photographs and a detailed listing of the contents. Fascinated by the offering, Dr. Marx immediately cabled the book dealer to send the volume on approval. Thus began a tangled tale of four cities involving extensive detective work, correspondence and the search for stolen art, culminating in a lawsuit involving the Seminary and an international cast of characters.

When the volume arrived, Marx was overwhelmed by its unsurpassed beauty. Here was a remarkable compendium of Jewish knowledge and prayer: treatises on astronomy, philosophy, mathematics; moralistic fables akin to Aesop; Psalms, Job and Proverbs, all with commentary; daily Sabbath and holiday prayers; entries on Purim and Hanukkah, including narration from the second Book of the Maccabees; Pirkay Avot; moral poems for children; a perpetual calendar; poems for weddings, birthdays and other occasions; and the text of the Haggadah. In all, more than 50 religious and secular works were bound in the more than 800 vellum pages. There were 222 exquisite miniatures, over 500 ornamental titles, and countless illuminations. Unquestionably one of the finest examples of an illuminated Hebrew manuscript, the Miscellany was a sumptuous work of art encompassing in minute detail virtually every custom of secular and religious Jewish life.

But Dr. Marx was troubled. A renowned scholar, he had recalled seeing reproductions of a few of the pages of the Haggadah in an obscure bibliographic text written in 1898 and had read an account of the entire manuscript in a 1930 French periodical, Revue des Etudes Juives. Dr. Marx inquired of the Berlin book dealer regarding the provenance of the work. The dealer responded forthrightly: “The ms. has been given to me by a country squire who wishes to remain anonymous. The owner has given a written statement that the ms. is in the possession of his family since a long time.”

Now Dr. Marx was suspicious, for the article in the French periodical had attributed the work to the Rothschild collection. It had been explicitly catalogued as “Ms. Edmund de Rothschild, Paris, No. 24”!

During the summer months, detailed correspondence was exchanged between Dr. Marx and authorities in London, Paris and New York, as he persevered in his attempt to document the rightful ownership of the Miscellany. Marx wrote to Hannah Arendt, Executive Secretary of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., an international umbrella organization whose constituent members included: Alliance Israelite Universelle; American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee; Board of Deputies of British Jews; Commission of European Jewish Cultural Reconstruction; Committee on Restoration of Continental Museums, Libraries and Archives; Conseil Representatif des Juifs de France; Council of Jews from Germany; Hebrew University; World Jewish Congress; and the Jewish Agency for Palestine. One of the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction’s representatives in Wiesbaden reported that, initially, Baron James de Rothschild (the son of Baron Edmund) was “very reluctant to give a definite reply to queries on the question of whether or not any of his most valuable mss. might be missing.” He quoted a reliable source in Paris who suggested that perhaps Rothschild did not want to divulge family holdings. In actuality, Rothschild’s hesitancy may have stemmed from the fact that he could not identify the Miscellany because he himself had never seen it.

Early in the summer, Dr. Marx turned for legal advice and counsel to Alan Stroock, an eminent New York attorney. As Chairman of the Board of the Seminary, Stroock wrote directly to Baron James de Rothschild in London, formally informing him of the disposition of the manuscript and of Dr. Marx’s suspicions concerning its ownership.

Stroock sought to enlist Baron Rothschild’s aid in identifying the manuscript, stating unequivocally that, while the Seminary was anxious to purchase the Miscellany, under no circumstances would it enter into a transaction involving stolen art.

Rothschild, in turn, contacted Andre Blum in Paris, who had been the librarian/curator of the collection of his father, Baron Edmund de Rothschild. Blum confirmed (letter dated July 21) that he had personally catalogued the manuscript as number 24, but that, unfortunately, all of his records and notes relating to the collection had been stolen during the Occupation. This correspondence was forwarded to Dr. Marx at the Seminary.

The final evidence arrived in a letter from Eugene Weill, Secretary General of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Paris, to Hannah Arendt (which she forwarded to Marx on August 11). In it Weill identified the manuscript as #24, “probablement le plus precieux volume de toute la collection ROTHSCHILD.” The manuscript, indeed, the most precious volume in the entire collection, had been stolen by the Nazis; it belonged to the Rothschild family and appeared on the French list of the Commission de Recuperation Artistique as being claimed by James de Rothschild, Edmund’s son.

Under the circumstances, the Seminary could not purchase a stolen work of art, nor would they return it to the book dealer, who, in the meantime, was impatiently chafing at the bit because Marx had not yet responded to the original offer of sale.

How could the Seminary insure the legal return of the manuscript to its rightful owner?

The Seminary’s only recourse, according to Stroock’s considered opinion, would be to have Rothschild file a replevin suit (an action to try the right to ownership of the manuscript) in the Supreme Court of New York, with the Seminary as defendant. On the advice of Stroock, Dr. Marx informed the Berlin book dealer of these developments and of the Seminary’s legal intentions. The book dealer, who claimed to be of Jewish origin, responded immediately, “I ask you to believe me that I am most anxious to have the matter fully clarified, not only because of my personal sense of Justice, but because of the reputation of my firm that has been in existence for 50 years.” Repeated attempts on his part to contact the German “owner” were unsuccessful.

Baron de Rothschild retained a lawyer in New York; the case was brought before Judge Samuel H. Hofstadter of the New York State Supreme Court. In default of any evidence from the purported German owner, the judge ruled in favor of Rothschild on February 23, 1951, and ordered the return of the Miscellany. The book dealer was not implicated. To protect his integrity, the Seminary never divulged his identity.

The Seminary was to remain custodian of the manuscript until it could be delivered in person to Rothschild in London. During the interim, Marx tried through several channels to persuade Rothschild to allow the Miscellany to remain in the Seminary Library, either on permanent loan or through outright purchase. In a letter to Rothschild he wrote poignantly: “On the one hand, I am very happy to have been instrumental in identifying the manuscript as your property . . . On the other hand, I, as well as my colleagues . . . here have become so attached to the volume that, after giving it eleven months of temporary asylum, we find it difficult to part with it.”

Curiously, it was Rothschild’s wife, the Baroness Dorothy de Rothschild, who responded in a handwritten note thanking Dr. Marx for all his efforts on behalf of the family but apologizing that her husband could not accede to his request. It was the Baron’s wish that the Miscellany go to Israel, and it is now in the Israel National Museum in Jerusalem.

Dr. Marx must have been dealt a crushing blow by the letter. He had no choice but to comply with Rothschild’s wishes. In March 1952, on his way to Israel, Dr. Marx stopped in London to deliver the Miscellany to Baron Rothschild personally.

Marx, the persistent and learned detective, did not live to savor the fruits of his labor. The final chapter of the story was written in 1966, when Baron Edmund, the grandson of the Baron Edmund de Rothschild of the French side of the family, personally presented to the Seminary Library the Rothschild Mahzor, another magnificent 15th century illuminated treasure from the family collection. Bound in its original velvet cloth, it, too, is an exquisite example of Italian High Renaissance manuscript art. At the formal ceremony, Baron Edmund de Rothschild expressed his sorrow concerning the fire which had ravaged the Seminary Library and recalled with deep gratitude Dr. Marx’s effort in restoring the Miscellany to his family.

A final postscript: In 1985, Michael Falter of Facsimile Editions in London was granted permission by the Israel National Museum to have the Rothschild Miscellany disbound. In a process painstakingly developed by him and artisans in Milan, he has produced on parchment a facsimile edition of the Miscellany, true to size, hand bound on parchment with hand-applied silver and gold leaf. Four years in production, the facsimile has now been completed in a signed and numbered limited edition. The Seminary Library has purchased one, through the generous gift of Chairman of the Friends of the Library, Francine Klagsbrun, her husband, Dr. Samuel Klagsbrun, and her brother, Robert Lifton.

This Rosh HaShanah, the Rothschild manuscripts will finally be united under one roof – in the Rare Book Room of the Seminary Library – in their original Italian splendor.

OUTLOOK wishes to express gratitude to Dr. Mayer Rabinowitz, Seminary Librarian, for permission to reproduce photographs of the Rothschild Mahzor from the Seminary collection and to publish material from the archives of Dr. Alexander Marx; to Evelyn Cohen, Curator of Jewish Art; to Rabbi Jerry Schwartzbard , Special Collections Librarian; and to Dr. Menachem Schmelzer (who was Seminary Librarian when the Mahzor was acquired) for their assistance and cooperation in researching this article. The Rothschild Mahzor will be on public view at the Jewish Museum in New York City, beginning September 17, as part of the new exhibit: “Gardens and Ghettos: The Art of Jewish Life in Italy.”

Dr. Lynne Heller is Editor of OUTLOOK. Her ongoing study of illuminated manuscripts developed when she was enrolled at ITS in a Women’s League Institute course on Illuminated Hebrew Manuscripts, taught by Evelyn Cohen.

De l’Esclavage à la Liberté

Shalom – Avril 1990/Pessah 5750 – Vol. VIII

par le Rabbin Adin Steinsaltz, Jérusalem*

La Sortie d’Égypte est l’un des moments les plus décisifs que le Peuple Juif ait jamais connu dans son histoire. Non seulement l’Exode donne-t-il sa signification profonde à la fête de Pessah, mais encore occupe-t-il une place centrale dans presque toutes les fêtes juives, la pratique de nombreux commandements et l’ensemble de la littérature; tous nos rites ne sont-ils pas accomplis «en commémoration de la Sortie d’Égypte» ?

Cette importance pluridimensionnelle accordée à l’Exode permet d’étendre sa signification historique à un sens plus large. En effet, cet événement domine l’histoire juive, témoigne de la présence divine au sein du Peuple juif et constitue un élément de base nécessaire à la survie de celui-ci. La Sortie d’Égypte servira de modèle de référence pour les générations futures du peuple d’Israël. «Dans chaque génération, l’individu doit considérer qu’il a personnellement pris part à l’Exode». L’évocation quotidienne de cet événement dans nos prières, la répétition constante de la commémoration de ce miracle nous démontrent que, bien qu’historiquement le fait soit unique, il a une portée quasi éternelle dans la vie du peuple et de l’individu juifs.

«Souviens-toi du jour de la Sortie d’Égypte pendant toute ta vie». Ce verset nous enseigne le devoir de répéter et d’étudier l’Exode. Nous avons l’obligation d’en prolonger la portée jusque dans notre propre réalité, quelle que soit la génération dans laquelle nous vivons. Ainsi, au fil des générations nous répétons: «Nous étions esclaves de Pharaon et D’ nous a fait sortir de ce pays» pour nous rappeler que l’individu qui n’accomplit pas son propre acte de «sortie» garde éternellement le statut d’esclave de Pharaon, abstraction faite de l’époque à laquelle il vit et de l’endroit où il se trouve.

NOUS ÉTIONS DES ESCLAVES

«Nous étions des esclaves de Pharaon en Égypte». De prime abord, le concept de l’esclavage peut paraître fort simple à définir. Le cliché de l’esclave souffrant, humilié, battu et même torturé est tellement bien gravé dans nos esprits que le véritable sens de l’esclavage nous échappe. Certes, l’image de l’esclave soumis à son labeur et maltraité par des gardes reste vraie. L’esclave bénéficie d’une rému- nération minime en comparaison de son pénible travail. Mais l’esclavage doit-il véritablement et uniquement être compris dans ce sens ? Dans le monde actuel l’homme – à quelques exceptions près – se démène pour assurer sa survie matérielle. D’ailleurs de tout temps, l’homme fut contraint de travailler de toutes ses forces pour ne rapporter chez lui que le strict nécessaire à l’entretien de sa famille. De même que les travaux forcés ne définissent pas l’esclavage, l’abondance matérielle n’est pas synonyme de liberté. Esclavage signifie avant tout exécution du travail par l’esclave pour autrui. Celui-ci n’est plus maître de ses décisions et ne peut plus exprimer sa volonté. Il devient un simple outil de travail et perd sa véritable identité.

Pharaon abhorre l’idée d’une collectivité d’Israël puissante à l’intérieur de l’Égypte; il exprime sa crainte d’assister au renforcement moral du Peuple Juif quant à son identité et son indépendance d’esprit en disant: «Et le peuple quittera le pays d’Égypte». Pour éviter que celui-ci ne soit gagné par un esprit d’indépendance, Pharaon s’ingénie à l’occuper par des tâches servant uniquement les intérêts égyptiens. Ainsi le Peuple Juif répond-il au critère d’un groupe d’esclaves, qui n’existe que par son travail pour autrui, en l’occurrence les Égyptiens. Même si, après leur libération du joug égyptien et leur arrivée en Eretz Israël, les Juifs se voient contraints d’accomplir de lourds travaux dans un pays où pourtant «coulent le lait et le miel», ils agissent en tant qu’êtres libérés physiquement et mentalement, car tout ce qu’ils font, ils le font par eux-mêmes et pour eux-mêmes. La différence est absolument fondamentale. Malheureusement, on ne peut affirmer que la Sortie d’Égypte ait mis une fin absolue à l’état d’esclavage du Peuple Juif: le peuple d’Israël lors de ses périodes d’exil – parfois même sur sa propre terre – continue de vivre sous la menace d’un asservissement extérieur.

«SERVIR L’ÉTERNEL DANS LE DÉSERT»

Chaque fois que Moïse et Aaron se présentent devant Pharaon pour le supplier de laisser partir le Peuple Juif, ils expriment le désir de leur peuple de servir l’Éternel dans le désert. Les négociations tournent toujours autour de ce même point. A première vue, ce désir peut passer pour un simple prétexte. Le peuple d’Israël veut quitter l’Égypte et invente une raison plausible pour justifier son intention. Il n’en est pas ainsi. Cet argument fait très clairement ressortir le caractère inhérent à la Sortie d’Égypte, la voie menant de l’esclavage à la délivrance. Pharaon réalise parfaitement que l’acte de volonté de servir D’ rompt les chaînes de l’esclavage. Les vrais esclaves ne possèdent pas leur propre D’. En outre, l’esclave ne devrait pas avoir d’autres obligations que d’accomplir son travail, c’est-à-dire de servir son maître et se plier entièrement à la volonté de celui-ci. Mais aussitôt que l’esclave découvre l’existence d’un Seigneur dominant son maître, un Être Suprême qu’il a le devoir de servir, il cesse d’être esclave dans son for intérieur. Bien qu’il soit possible de soumettre des hommes à des travaux forcés pendant une période prolongée, les travaux de ce type n’entrent plus tout à fait dans la définition de l’esclavage. La révolte nécessaire à la libération est un processus lent dont la réussite est assurée à condition que l’esclave persévère dans sa volonté de servir l’Éternel dans le désert. A juste titre, Pharaon reconnaît que la volonté de servir D’ annonce le relâchement de l’esclavage et décide donc au moyen de travaux forcés, d’une part de réprimer le sentiment nationaliste des Juifs et. d’autre part. de les opprimer moralement. La Sortie d’Égypte à proprement parler ne représente pas une menace, mais elle n’exclut pas l’esclavage. Il y a déjà véritable libération du moment que la volonté de partir avec un but bien défini existe – à distinguer de la volonté de fuir les travaux forcés. Cette aspiration au départ signifie le rejet d’un mode de vie d’autrui, d’une morale imposée et de ses valeurs. Les diverses tentatives entreprises par le Peuple Juif pour échapper à l’exil ne menèrent à aucune véritable délivrance. L’homme qui ne possède pas d’identité ni de personnalité et qui n’a pas son propre D’ reste esclave. La libération inclut l’existence d’un système de valeurs indépendant, où l’absence de l’esclavage est sans doute significative, mais n’est que le début de la liberté. La rupture du joug égyptien n’entraîne pas nécessairement une vraie délivrance, le Peuple Juif y parvient par le reniement de l’Égyptien et de son système de valeurs. L’importance de la Sortie d’Égypte se traduit par le culte rendu à D’ dans le désert. Une fois la voie de son mode de vie tracée, nettement distincte de l’esclavage, le Peuple Juif accède à la liberté.

ENTRE PHARAON ET LE DÉSERT

La Sortie d’Égypte, passage de l’esclavage à la liberté, est un long processus. Lorsque finalement le Peuple Juif sort d’Égypte avec ses propres chefs et ses propres armes, la délivrance pourrait être considérée comme complète. Mais l’heure de la vérité ne tarde pas à sonner au moment où le peuple se trouve en situation de détresse. Il apparaît subitement que ceux qui réagissent avec une mentalité d’asservis restent victimes de cet état même après avoir fui l’esclavage. Où est donc l’esprit de fierté ? Où est le sentiment de confiance en soi ? Le peuple demeure un peuple d’esclaves, car il exprime clairement sa nostalgie de l’assujettissement lors de situations difficiles. L’incapacité de mener une vie indépendante et l’échec d’une délivrance intérieure sont frappants. Il devient insensé pour le Peuple Juif, un peuple d’esclaves. da vouloir mener une guerre contre Pharaon et d’errer dans le désert. car ces actes requièrent un esprit d’indépendance totale.

La libération à part entière et la maturité engendrent la volonté d’atteindre l’impossible. Le miracle en est la conséquence. Mais, pour que le peuple mérite d’assister au miracle, il doit être prêt à mettre sa liberté en jeu. Ce n’est que lorsqu’on risque l’impossible qu’on le rend possible.

* Le Rabbin Adin Steinsaltz est considéré comme l’une des plus éminentes autorités rabbiniques de notre époque. Auteur de nombreux ouvrages, il consacre aujourd’hui sa vie à la diffusion du Talmud dont il a déjà traduit vingt volumes de l’araméen en hébreu, y incluant ponctuation et intonations. Il travaille actuellement à une version anglaise et il est question de publier une édition en russe. Il poursuit ses travaux dans le cadre de l’lsrael Institute for Talmud Publications à Jérusalem. En 1988, le Rabbin Adin Steinsaltz a été invité à ouvrir l’Institut d’Études Juives à Moscou. Il a par ailleurs enseigné à Yale University et à Princeton.

Bodleian’s unbroken Hebraica tradition

Jewish Chronicle – July 1 1988

Richard Judd – Assistant librarian, Bodleian Library

The Prince of Wales is guest of honour at a dinner at the Bodleian Library, Oxford, next Tuesday to launch a £12 million appeal to renovate and modernise the library and endow new appointments to its research staff. Presiding over the dinner will be Lord Jenkins, Chancellor of Oxford University.

THE ORIGINS of the great collections of the world, in Hebraica just as in other subjects, usually lie in the efforts of individual collectors.

After a lifetime of single-minded collecting, the individual decides to place his treasurers in an institution so that they can be preserved intact. Or sometimes, after his death, his family present the collection so that it can be named after him.

The Bodleian Library in Oxford has received benefactions in many subjects through such channels, but its Hebraica collection is unique in that it was a principal constituent of the library from the outset.

At first sight, it may seem odd that such a substantial collection of Jewish books should have been started in 1600, when officially there were no Jews in England. But Sir Thomas Bodley, who refounded the university library in 1598, was a type of man now almost, though not entirely, extinct.

A fervent Protestant, he was an accomplished linguist who knew the classical and modern languages, “but Hebrew particularly, the parent of all the others.”

It is astonishing how many Hebrew books arc listed in the first catalogue of the library, printed in 1605; they arc overwhelmingly from Venice, where Hebrew printing was then in its prime.

Bodley took a detailed personal interest in these books, and one can still see at the end of the catalogue a page largely in Latin where he indignantly corrects some misprints in Hebrew.

The continued policy of collecting Hebrew material bore sensational fruit in 1693, when the library purchased two different collections which still attract a continuous stream of Jewish readers.

Item 80 in the collection of manuscripts bought from Dr Robert Huntingdon is Maimonides’ “Mishneh Torah,” with the author’s signature, attesting that the text had been corrected. against his original.

This manuscript is supremely important both for historical reasons and for the accuracy of its text; it is treated with great reverence by scholarly readers. Huntington bought it while acting as chaplain to English merchants in Aleppo.

A second Maimonides manuscript, this one in his own handwriting throughout, came as number 295 of the 420 manuscripts bought from Professor Edward Pococke, the Regius Professor of Hebrew. It is the “Commentary on the Mishna,” containing the tractates Nezikin and Kiddushin.

It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of these manuscripts for establishing the correct text, particularly since autographs of any medieval Jewish scholar are exceedingly scarce. It is sobering to reflect that, for both collections„ comprising 1,020 manuscripts in all, the university paid only £1,300.

One of the most sumptuous Hebrew illuminated manuscripts in existence, and a masterpiece of medieval Sephardic art, came to the library in bizarre circumstances in 1771.

A young gentleman, Patrick Chalmers, entered the library carrying a Hebrew Bible written in 1476. Dr Benjamin Kennicott immediately recognised its importance and bought it for £52.10s.

The Bible had been copied by Moses Ibn Zabarah and lavishly illustrated by Joseph Ibn Hayyim on behalf of their patron, Isaac di Braga. It was truly an exquisite production, an exact facsimile of which was published in London in 1985. No one has any idea where the original lay between 1492 and 1771.

In 1829 an event occurred which was to turn the Bodleian Library into a depository for the most important and magnificant Hebraica collection ever accumulated. This was the purchase of the famous Oppenheimer Library for £2,080, a price later described as “the best bargain in the history of bookselling.”

Rabbi David ben Abraham Oppenheimer (1664-1736) was the Chief Rabbi of Prague, who devoted more than half a century to building up his library. A bibliophile fromhis early youth, he went on long journeys to obtain rare manuscripts or books.

Oppenheimer visited the fairs at Leipzig, was in close touch with printers and dealers and spent lavishly from his great wealth (inherited and received from his wives). He collected manuscripts with a view to subsidising their publication.

After his death, however, the collection was the subject of litigation, being held in storage in 28 crates in a Hamburg warehouse. This deeply concerned the scholars of the Wissenschaft des Judentums, particularly Leopold Zunz, but no one could be found who was willing to donate the collection to a library.

Although Moses Mendelssohn had valued it at between 50,000 and 60,000 thalers, it was finally sold for the ridiculously low sum of 9,000 thalers (the £2,080 in question) to the Bodleian Library.

This collection, of over 5,000 books and manuscripts, contains the best library in the world of Old Yiddish books from the 1530s (the beginning of Yiddish printing) onwards; in a number of cases, it includes the only surviving copy.

When the Oxford Centre for Postgraduate Hebrew Studies was founded in 1972, the founders hoped that the Centre would facilitate and co-ordinate the essential research on the collection, ‘which also contains a vast amount of rabbinic writing, particularly responsa, some of it by Oppenheimer himself and much of it still unpublished.

The situation described in the “Annals of the Bodleian Library” for 1829 still applies — that the library is “never without several foreign visitors engaged in its examination.”

Subsequently, the Bodleian has been continuously active in acquiring Hebrew material. It had the good fortune to have on its staff two of the greatest Hebraists of all time — Dr Moritz Steinschneider (18161907) and Dr Adolf Neubauer (1831-1907). Their great catalogues, of respectively Hebrew printed books and manuscripts in the Bodleian, will remain standard works for the study of Hebraica.

Further significant collections of Hebrew manuscripts were added in 1848, 1890 and 1981, while many incunabula — books printed in the fifteenth century — were acquired in Victorian times.

Even today, the library selects and acquires hundreds of the latest Hebrew books from Israel every year, so that there is an unbroken tradition of collecting Hebrew books from Bodley to the present.

Ibn Zabarah’s blessing

The Jerusalem Post Magazine – Friday, March 1, 1985

Emmanuel Pratt

MOSES IBN ZABARAH dipped his stylus in the rich brown ink and was about to apply it to a folio of thin, crisp parchment almost completely filled with clear, square Hispano-Jewish script. But he did not touch it. He preferred to linger and muse.

This would be the concluding paragraph of his colophon to the Book of Books he had copied from beginning to end during the last 10 months. He looked with satisfaction at the pile of similar folios stacked on the desk. A total of 460 sheets, one more beautiful than the other. And now he was about to complete the last one, the 461st.

He let his mind wander further into the past. Yes, he had come a long way since those days when he started out as an obscure travelling scribe, going from one Jewish community to another throughout Spain in search of a patron who would commission him to copy some manuscript or other.

He also had a great dream: to create his own manuscript — a true, vocalized copy of the traditionally accurate Bible that would be of incomparable beauty in script and illumination. Even more beautiful than the famous manuscript written in Cerbera in the year 1300 CE.

And now the dream was fulfilled: he, Moses Ibn Zabarah, and the artist Joseph Ibn Hayyim, had written and illuminated a book which could compete with the manuscript of Samuel ben Abraham Ibn Nathan and Joseph the Frenchman of Cerbera. Compete, and perhaps surpass.

He knew, however, that the dream could not have been fulfilled but for his young, rich and ambitious patron, Yitzhak Ibn Don Solomon di Braga di la Coruna. Yitzhak had seen the Cervera Bible. His late father’s library contained many precious manuscripts, but he had never seen one equal to this in splendour. A passionate lover of books, he ached to acquire it. But the owner would not part with it at any price. And so he made a decision: he would create his own manuscript, and it would be even more beautiful, more richly decorated.

Thus it was that Moses Ibn Zabarah now sat, stylus poised, ready to pen the dedication of his completed work to his patron:

“The admirable youth, Yitzhak son of the late honourable and beloved Don Solomon di Braga di la Coruna. The blessed Lord grant that he study it, he and his children and his children’s children throughout the generations… and God enable him to produce many books, books without end.”

Obviously Moses Ibn Zabarah looked forward to obtaining more commissions from his patron, especially as it seems that he had previous connections with the Braga family, and it may well he that it was he who influenced Yitzhak’s decision. Joseph Ibn Hayyim was engaged to illustrate’ and illuminate the manuscript, and the work began.

Judging by the magnitude of the project, it is safe to suppose that Jospeh Ibn Hayyim was a well-known artist, and that he was well acquainted with the Cervera Bible, whose influence can be seen in many of his illustrations. What is certain is that he was a great artist in his own right, inspired by his own imagination both in style and motifs.

The two men worked in close cooperation, the scribe planning the layout and allotting the spaces for illumination, as was customary in the production of medieval manuscripts. Now the work was complete.

The scribe dipped his stylus in the ink once more and wrote his closing words: “Blessed be he who preserves this book in his treasury. It should be kept for the children of Israel for generations… Amen.”

The date of the conclusion of the work was subtly coded by accentuating certain letters in the text of the last paragraph of the colophon. They added up to read: the third day of the month of Av in the year 5236 from the Creation. In terms of the Gregorian calendar, this meant July 24, 1476.

The sky was dark. Through the open windows the scribe heard monotonous chanting approaching. A procession of white-robed Dominican friars, torches in hand, passed along the narrow street below. The chanting died away, and soon a glow appeared in the sky. In the central square of Coruna a great bonfire had been lit. In it books were being burned. The Spanish Inquisition was on the march.

THE FATE OF Yitzhak Ibn Don Solomon’s library, as of the young man himself, is unknown. But the beautiful manuscript escaped the. flames, to lie hidden, no one knows where, for nearly three centuries.

On April 5, 1771, a certain Patrick Chalmers walked into the Radcliffe Trustees Collection in Oxford with the manuscript in his hand. He was offering it for sale, and on the advice of the librarian, Dr. Benjamin Kennicott, the Radcliffe decided to purchase it. Patrick Chalmers, Esquire, returned to obscurity richer by 52 pounds, 10 shillings.

Kennicott well knew what he was buying. A canon of Christ Church Cathedral and a learned Hebraist, he had studied hundreds of Hebrew biblical manuscripts from all over Europe, comparing their textual variations. His young wife, Hannah More, studied Hebrew to assist him in his ambitious research to ascertain “the accurate Hebrew text of the Bible.”

The Ibn Zabarah manuscript was never part of Kennicott’s personal collection. However, when it was transferred to Oxford University’s great Bodleian Library in 1872, it was registered as “Kennicott One.”

ANOTHER 108 years passed in twilight, with only the privileged experts having access to the exquisite manuscript. Until early in 1980, a young London printing engineer, Michael Falter, spent a leisurely Sunday afternoon visiting a permanent display of ancient Hebrew manuscripts in the British Library.

Michael Falter has a long family printing tradition “It goes back to the time when my great-grandfather was a travelling salesman in Czechoslovakia going on his bicycle from one town to another, selling type to printers,” he told me. His grandfather had a printer’s shop in Prague, and his father, a printing engineer, moved first to Vienna, and then, as a refugee, to London, where he started a printing machinery business.

Michael has a fascination for antique printing presses. He acquired two more than a hundred years old, planning to use them to reproduce printed works in the same way as they were originally produced. Some years ago he went to see Dr. David Patterson, chief librarian of the Bodleian’s Oriental collection, but the plan did not materialize. Now, in the British Library, the idea returned. and he paid another visit to Dr. Patterson, who invited him and his fiancée, Linda, to look at the “Kennicott.”

They were stunned by its splendour. And yet there was something else – a challenge and a cry from the distant past: “Blessed be he who preserves this hook in his treasury. It should he kept for the children of Israel for generations… Amen.”

That was an injunction that had never been fulfilled. He, Michael Falter, would fulfil it. He would make it possible for Jews all over the world to admire and study it. He would produce an exact facsimile of the Kennicott Bible.

“It is difficult to describe the extraordinary feeling we had at that moment,” says Michael. “We decided there and then that this was the manuscript we wanted to make a facsimile of. No other. This would be our first. Kennicott One would be Falters One.”

And Falters One would be produced in 550 copies.

THE FIRST thing was to secure a contract from Oxford University. It was a two-year battle. “We had no previous works to show them,” says Linda, “and we didn’t even know then that the library itself was bidding for the same project.”

Why was the Bodleian interested in making a facsimile of one of its most treasured gems? Would it not lower the value of the original?

“The original has no price, so it cannot be diminished,” she replies. “But every time somebody uses the manuscript it deteriorates in some way: there is wear on the binding, there is wear on the pages. And if no facsimile is made, it will eventually disappear. It will fall apart and they will have to lock it away and nobody will see it. And without blowing our own trumpet, we are actually performing a very valuable function for the library by producing this facsimile for them.”

When the Bodleian finally had to admit that they were abandoning the project because it was impossible to produce an exact replica of the original, Michael and Linda were given the contract.

NOW THEY were on their own to cope with problems that seemed insurmountable. The first was the paper:

“As far as we have seen,” says Linda, “facsimiles normally don’t give the feel of the original manuscript because of the quality of the paper. We wanted to produce a work that would have not only the look but the feel of the original, and so we had special paper milled for us. It had to have the translucency of parchment, so that the text and the illumination on the other side of the leaf would show through just slightly. It must not be smooth, and it must not be rough. Our facsimile was to be printed on a miracle. And it was.”

Most of their battles the couple had to fight on the Continent. “We went all over Europe looking for printers and paper,” says Michael. “For about a fortnight non-stop we were seeing two printers a day.”

No sooner was one problem solved than another emerged. The major one was the box binding. The original Kennicott One manuscript, in spite of its five centuries of wandering, is still in very good condition. This it owes to the magnificent box-binding in which it is enclosed: the soft goatskin is stretched over wooden boards which protect it from all sides.

“We have excellent hinders in England,” says Linda, “and assumed that we could get very good craft binding at home. It took us six months to discover that the best binder in England could not produce work anywhere near good enough. We went as far as Milan to find one. It was our own printer, in fact, who introduced us to him.”

The Italian printer proved to be just as much of an enthusiast for the project as he is a perfectionist.